The Learning Corner

Throughout the year, our teachers engage in Continuing Education focused on bettering themselves as preschool educators and service providers. Part of this Continuing Education is provided by our Group Teachers, Barbara Harbaugh and Cindy Babetski. Each week, Barbara and Cindy send out relevant, fresh articles aimed at enhancing skills, building confidence in the classroom, and empowering our teachers to uplift our preschool students. In this section, we have compiled some of the articles for you - so you, too, can learn why our philosophy of play and engagement is SO important for our young learners. Enjoy!

What is Play-Based Learning?

by The Brightwheel Blog

- Tell me about the structure you’re building.

- Why did you choose those blocks?

- What do you think might be your next step?

Fine Motor Activities for Preschoolers

by Vanessa Levin

What are Fine Motor Skills?

The term fine motor refers to the small muscles in the hand and fingers. While some fine motor skills may develop naturally through daily play, it’s important to be intentional when it comes to strategically planning opportunities for your kids to practice these skills daily in the classroom.

Why are Fine Motor Skills Important?

Young children must exercise these muscles often in the early years so they can do daily tasks in the future like writing, tying shoes, buttoning, zipping, and other self-help skills.

It’s important that your toddlers and preschoolers have plenty of opportunities to work on fine motor development to prepare their little hands for the tasks listed above. Before children can begin to hold a pencil in their hands and write with control, they must first develop strength and dexterity in their fingers and hands.

You can help your children develop fine motor skills by providing fun, engaging activities in your classroom like these that encourage using the hands and fingers together.

Fine Motor Activities for Preschoolers

Everybody knows that kids learn best through play, and what could be more playful than stickers? Stickers are super popular with the littles. Why not harness their natural fascination and invite them to use stickers as a way to practice those fine motor skills? They’ll think they’re just having a good old time!

Did you know you can often find inexpensive golf tees at the dollar store? Invite your kids to hammer golf tees in playdough, or even a pumpkin in the fall for super engaging fine motor fun!

Rolling pins are the first of many kitchen items on this list that can be used for fine motor development. As your kids roll the ends of the pins against their palms, they’re massaging the arch in their hands known as the palmar arch. This arch is super important for hand strength development in young children.

If your kids aren’t quite ready to cut paper, then try dough scissors. Cutting play dough with dough scissors is super fun, but also excellent for developing fine motor skills – and it’s perfect for cutting practice too!

The possibilities for using clothespins to develop hand strength are endless. Use inexpensive sets of socks from the dollar section of your local big box store or raid your laundry basket for old socks. String a piece of yarn or twine between two chairs to create a mini clothesline and your littles will have a blast hanging socks. In fact, they’ll be having so much fun they won’t have a clue that they are actually practicing an important skill.

There are lots of things in your kitchen that can be used for fine motor practice. Kids love using tongs to pick up small objects like pom-poms to transfer into ice cube trays.

While geoboards are often thought of something used in math instruction, they’re also perfect for developing those little hand muscles.

Another common household item that can serve double duty for developing hand muscles is a plant sprayer. You can find inexpensive plant spray bottles at your local dollar store. Your kids will have a blast spraying water on the grass at recess or add a little liquid watercolor and invite them to spray the snow if you live in a cold climate.

Stringing beads on a pipe cleaner is a great way to support fine motor development in your classroom. You can invite your preschoolers to thread small pieces of paper straws onto chenille stems. If your children are old enough you may consider adding some pony beads to your fine motor tray.

Have your kids ever used eye droppers or pipettes to color coffee filters? This is a great open-ended art activity that also doubles as fine motor practice. Place some liquid watercolors in a shallow container and invite your students to use eye droppers or pipettes to drop the colored water onto coffee filters. The water quickly absorbs into the coffee filters and creates beautiful designs.

Using tongs is also a great way to practice those hand muscles. Children can use tongs to pick up items and transfer them from one container to another.

Invite your kids to twist chenille stems (pipe cleaners) and place them into a colander to develop fine motor skills. Bonus, this activity is also great eye-hand coordination practice.

Have you tried crayon resist painting with your class? Invite your kids to put masking tape on white paper, then paint over it with tempera paint. As if playing with tape and painting wasn’t fun enough, invite your kids to peel the tape off the paper and reveal the white space underneath – what’s not to love?

Any time you can add tweezers to an activity you’re getting a little bit of easy fine motor practice. I love Gator Grabbers because they’re perfectly sized for little hands, they’re easy for kids to use, and they have grips which help with picking up objects. My kids adore using tweezers to pick up pom-poms or any small objects and placing them in ice cube trays. You can even add dice to this activity and have them roll and count out the number of items into the tray, filling one space at a time.

Have you ever used Q-Tips for painting in your classroom? Painting with cotton swabs is great fine motor practice because you have to grip them the same way you would grip a pencil. Grasping the swabs, dipping them in paint, and tapping them on paper is a super fun and inexpensive way to paint.

A hole punch or shape punches are super fun for kids! Just put out some punches in your writing center along with some colorful construction paper scraps and invite your children to start punching away. You’ll be surprised by how long this seemingly simple task will keep them engaged. While it may seem simple, paper punches are excellent for fine motor practice.

One of the most popular fine motor activities for kids is lacing beads. When it comes to developing fine motor skills in the preschool classroom, lacing beads are the gold standard. Young children also develop important hand-eye coordination skills when lacing beads.

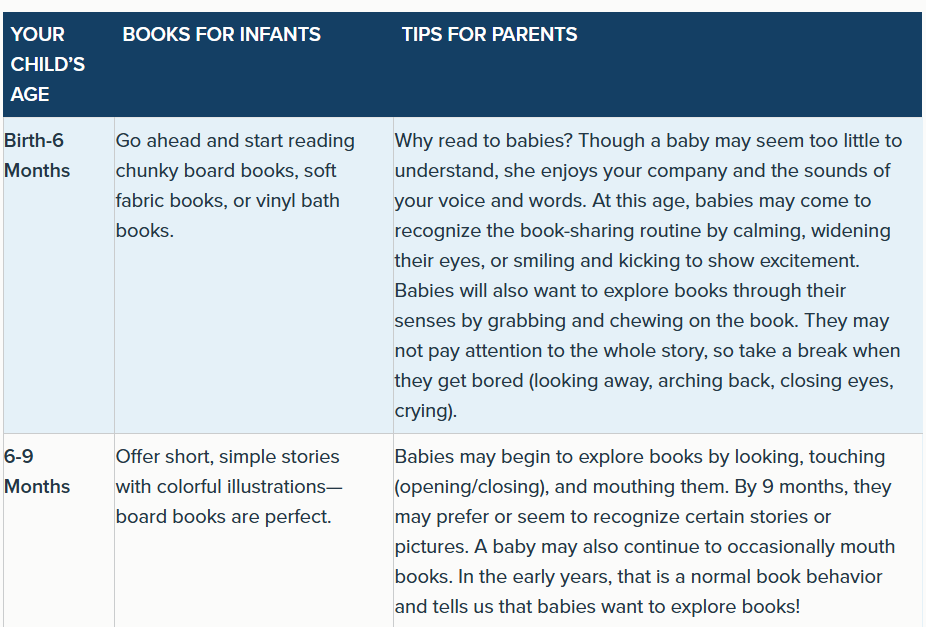

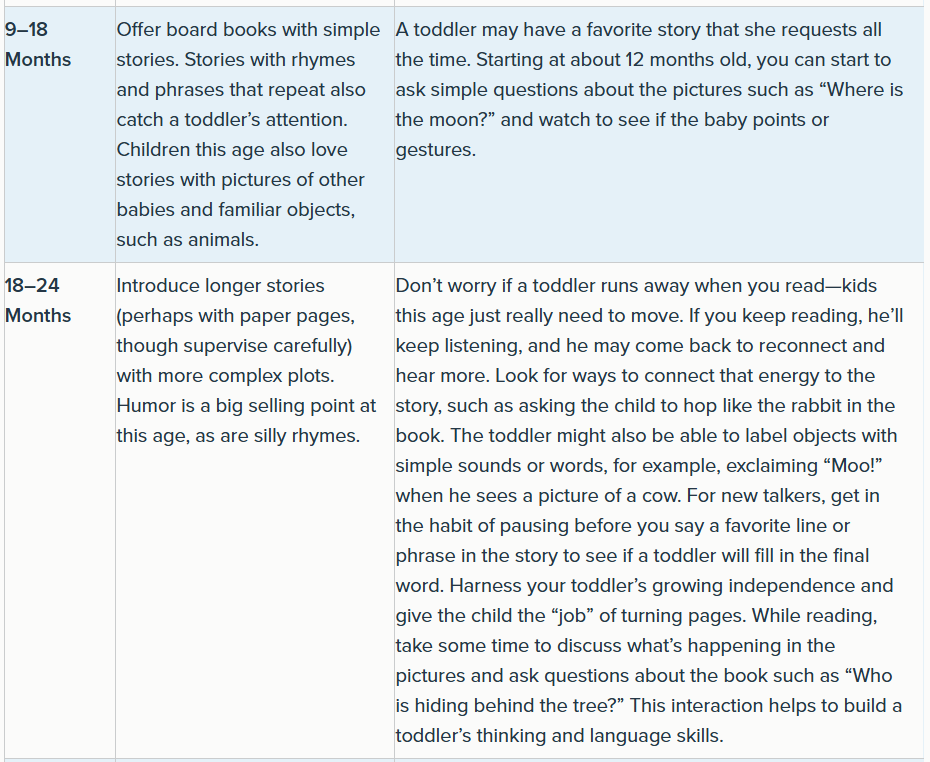

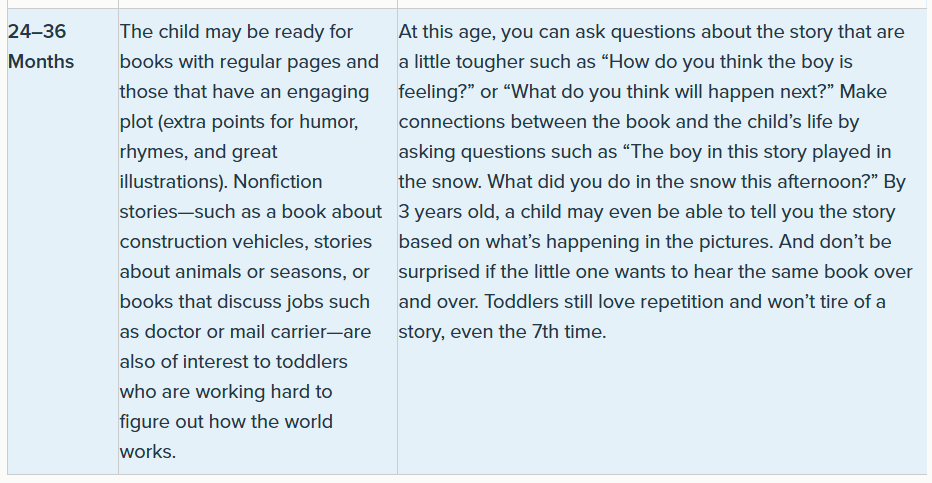

Read Early and Often

by Rebecca Parlakian and Sarah S. MacLaughlin

10 Benefits of Songs with Hand Motions

by Woo Therapy

Do you remember when, where, and how your love music first started?

For me, as a little girl, I remember two very distinct happenings that catapulted my love of music. First, was the steady rotation of REO Speedwagon, Madonna, STYX, and Amy Grant on bimonthly road trips to visit my grandma for nearly 2 decades. And second, I remember incessantly singing, reciting, and performing my favorite Pre-K song, “I’m Bringing Home a Baby Bumble Bee” every single day to anyone who would listen.

And just like me, my 4-year-old is now the one coming home with new songs from preschool to teach his little brother.

From the Beatles to the Jonas Brothers. From 90’s hits to worship music. And everything in between, we love it all!

We even blast those sing-songy children’s tunes. You know, the ones that get stuck in your head for days? The ones with little hand movements, counting, and rhyming words. Or the ones where you touch your nose, clap your hands and turn all about. Then there are even the ones with the goofiest lyrics. Makes you wonder how in the world someone could even come up with it?

But as an OT, I totally welcome it. I sing, dance, and demonstrate songs and movement all day for my “little friends” at work because I know and believe in the incredible benefits of songs with hand motions. So why wouldn’t I do exactly the same for my own children?!

Nursery rhymes, fingerplays, circle songs, movement and hand songs, whatever you want to call them, “I. LOVE. THEM!

On the surface, they might seem simple, or at times annoying; but there are so many rich and important skills that develop while learning, performing, and repeating those silly songs.

Creating and fostering interest and love of participating in these fun kid songs nurtures so many skills that many kids these days are honestly lacking.

But why are songs with hand motions so great?

Imitation of actions and speech is thought to be an innate ability we are born with. That imitation is a form of learning. Seeing and then doing (or not doing based on the outcomes observed of that action) teaches us about our bodies, our environment, and those around us.

Fingerplays and hand songs are a fun, easy, and engaging way to encourage your child to repeat the demonstrated movements of your body (head, arms, hands, legs, face, etc.), learn the lyrics of the song, and explore the relationship between their body and environment.

- Side note: If there are balance or mobility issues, start with songs that can be done in a seated position. Remove the elements of difficulty so your child can focus solely on the imitation aspect.

Keep it fun, light-hearted, and follow their lead. If your child says “More!,” hit repeat. If they seem to not enjoy a certain song, change it up.

2. Range of Motion

Lots of these songs incorporate every body part from the head to the toes. A child might need to reach, twist, shake, bend, clap, stomp, turn, bow, snap, etc. any of their various body parts at any moment.

3. Fine Motor Skills

There are so many small muscles in the hand. Each of them needs tons of repetition of various movement patterns and positions to improve dexterity and automaticity. Finger songs are awesome for targeting lots of fine motor movements such as a pincer motion, finger isolations, forearm rotation, finger stretching and strengthening, coordination, and more.

For example, think about songs involving counting and how quickly (or not so quickly) a child can display the corresponding number of fingers they are singing about without the use of their other hand. This takes practice and perseverance.

4. Counting/Number sequence & recognition

Many of the songs we sing at our house involve counting. And actually, many of them count backward. I’d encourage you to help your child learn all the numbers in proper sequence before introducing counting backward.

We like to sing 5 Green and Speckled Frogs, 10 in the Bed, 5 Little Ducks, etc. Counting both forward and backward have their benefits. As a child sings and pairs the words with the number of fingers held up, they can begin to not only develop the previously mentioned fine motor skills but start to create awareness and automaticity of numbers and improved 1:1 correspondence (a critical skill in Kindergarten).

For example, if we start singing 5 Little Ducks by also holding up five little fingers, a child will start to create an association that a hand holding up all fingers represents or equals the number five and so on for each number as you work your way through the song.

This is the ability to focus on an activity or stimulus over an extended period of time. It is what makes it possible to concentrate on an activity for as long as it takes to finish it, even if there are distracting stimuli present.

I think this is a skill many people overlook in little kids. Most people just think “it will come in time” or “my child is only 3, what do they need to focus on for more than a few minutes anyway.”

And yes, while it’s no secret that children between 2 and 5 tend to have short attention spans (some as short as 10 seconds); attention is a skill that needs to be fostered and expanded through play and learning; not through technology!

Songs with hand motions are a great tool for improving the length of a child’s engagement as they have a clear beginning and end. They also have rhythm, use silly words, facilitate social experiences, and hopefully develop an intrinsic desire for a child to complete the full sequence of events; however long the song may be.

Which leads us to…

Sequencing is a critical life skill. It is the ability to arrange information in an effective order to achieve the desired outcome. Dare I say, everything requires the ability to sequence. From pouring a glass of milk to tying shoes to driving a car. Actions must be arranged in a first, next, last order; oftentimes with upwards of 10+ steps to reach the intended outcome.

Through sing songs, a child will anticipate the sequence of events based on what they remember through the repetition of each song. Therefore, songs with hand motions also require memory. Kids must organize and reorganize the information during each future attempt.

For instance, during everyone’s favorite the Hokey Pokey; one must remember to put your left arm in before you put your left arm out. And one must shake it all about before they do the Hokey Pokey and they turn themselves about.

It’s quite difficult for a child to perform that song with proper sequencing on the first, second, or even third time imitating it. They must hear it and do it several times to start memorizing and sequencing the steps for a successful performance. And even then, it will require sustained attention to listen for the body part as well as imitation skills to properly correct and catch up with the group, should they make a mistake.

7. Body Part Identification

This one seems obvious, but necessary to share. Because certainly you can teach your child to point to their nose or their toes or their elbows while hanging out in the living room after dinner. But is it as fun and engaging as dancing and singing with them for a quick pre-PJ wiggle sesh? Not even a little bit.

Children will start pointing to and labeling body parts between 12 and 18 months. But at that age, what length of time do you anticipate they will sit (or stand) with you while pointing to different body parts? Obviously, every child is different, but my boys would do 3-4 body parts within 15 seconds, then be up and off to the next thing.

By using music and movement, I can get them to participate for up to 30 minutes in these songs all while learning where their ears, elbows, and chin are!

Hello, sustained attention!

8. Speech

This is a biggy! SPEECH SPEECH SPEECH! Songs encourage frequent and continuous opportunities to get their mouths moving. Whether you are wanting to help your child increase his vocabulary or improve articulation; music and songs are an easy and motivating way to do so.

Music is a powerful tool. One that I know nearly all speech therapists use within their practice.

9. Social Skills

This kind of falls under the speech umbrella but there’s so much rolled up in social skills; maintaining eye contact, body language, facial expressions, proximity to peers while performing gross motor movements, tone of voice, reciprocating song lines, encouraging peer participation, etc. There are many opportunities for children to share experiences by singing a song as a large group, without the pressure of figuring out what to say or how to say it.

I always think of the shy kid who doesn’t say a word in class but the beat drops, and he’s singing, jumping, and smiling. By participating in these songs with hand motions, this allows the other children to see that the shy kid actually does like school and definitely wants to be part of the group but just isn’t sure how or needs time to warm up.

10. Prepare for Table Top Tasks

If songs with hand motions or movement activities are not a part of your classroom schedule, they need to be! Before instructing your child (or a classroom full of children) to sit down you need to get them moving!

Movement songs are beneficial in preparing the whole body for the tasks that lie ahead. They get the wiggles out, stretch the muscles, activate the core, regulate the breathing, stimulate the brain, arouse the eyes, and coordinate the fingers.

Additionally, the children receive the transition to a less preferred activity much better than a command to “sit down.”

Songs with hand motions provide an opportunity for a child to release any tension, frustration, and anxiety that might be evoked by merely suggesting a sitting activity.

Give it a try and see the difference. Notice your child’s engagement in non-preferred tasks. Notice the overall regulation of your child. And notice the quality of their work when you offer them a chance to organize their body and brain before requiring increased academic demands.

As you can see, songs with hand motions and movement breaks are incredible. No matter the age of your child, there is something you can observe and improve in them when you take the time to engage in these fun, simple, and silly songs.

When I watch a student memorize the lyrics or master the hand motions of a new song over the course of a few days or weeks, I beam with pride.

And when I catch them singing the songs to themselves as they perform the motions—I melt!

8 Easy Math Games for Toddlers

by Parents Editors

Learning to count is a great introduction to mathematics for toddlers. Counting fingers and toes from one to ten is particularly fun when accompanied by rhymes such as "one, two, buckle my shoe." Aim to work counting in throughout your day, such as lining up toys on the floor or pieces of finger food on their plates for them to add up.

2. Sort Objects

To help your child understand groups, you can sort things based on categories, such as color, size, shape, texture, or use. For instance, have them separate their toy cars from toy airplanes or spoons from forks. They can also sort building blocks by color or size, and then count how many are in each group.

3. Set the Table

Teach your child that mathematics has real-life applications too! Setting one plate for one person, two cups for two people, and so on helps your toddler learn important skills. They can also help with cooking, such as asking them to get four carrots, three apples, or two eggs.

4. Name Shapes

The naming of shapes is fundamental to your child's understanding of math. Play a game of finding squares and circles around the house. For example, point out your circular clock, square blocks, rectangular toaster, etc. Also, show them how triangles can fit together to make a square and smaller objects can fit inside larger ones, such as bowls or cups.

5. Teach Spatial Relationships

Play games that teach the concepts of “near and far” or “under and over.” For example: Walk towards me when I say “near,” and backward when I say “far.” Climb over the chair and under the table. Also, let your toddler practice volume and quantity by filling cups with water or sand, and transferring contents from one container to another.

6. Compare Sizes

Here’s a math game for toddlers that teaches size: Ask your child to gather their stuffed animals, then line them up from smallest to largest. You can also encourage your child to stretch as big as they can and then curl up to make themself tiny. Talk about how people of different ages have different sizes, pointing out that you are bigger than your toddler and that they are bigger now than when they were born.

7. Teach Patterns

Patterns are also an important math concept for toddlers. Set up the start of a simple pattern of blocks or other toys in alternating color or shapes and let your child add on. Puzzles, building bricks, magnetic building tiles, and lacing toys also build on these skills of observation, repetition, and construction.

8. Use Math Concept Words

Phrases that denote quantity, like "a lot" and "a few," begin to take on meaning when used in everyday conversations. Make a point to include these phrases while grocery shopping, eating dinner, and playing games. Ask your child how many of an item they can see or whether they have more of one type of item or another.

The Importance of Sharing Holidays You Don't Celebrate in Preschool

by Makinya Ward

Do you wonder why preschool introduces holidays you may not celebrate? When preschool teachers and parents teach children about holidays from a variety of cultures and beliefs, they are helping children to develop empathy and understanding for other people and ideas.

With every year that passes, it seems that there are more and more tragedies occurring in this country and around the world, that serve as constant reminders that we must do more to instill tolerance, acceptance and love in our children. The holiday season is an amazing place to start to open your child's mind to cultures and traditions outside of their household and help them understand and celebrate the differences in our world.

Here is why explaining various holidays to preschoolers is important.

Holidays Teach Similarities

Most holiday celebrations in every culture focus on teaching traditions, history, and the reason a group of people cares for one another. Teaching children about the holidays of other cultures helps them to see that no matter what differences we all have, we also have many things in common, such as:

- Family: Most holiday celebrations are times when extended families gather together to enjoy special food, traditions and one another.

- Respect: Most cultures use holiday celebrations to honor their history and past. By explaining holidays to preschoolers, teachers and parents can help children to understand and respect the sacrifices of people in history.

- Love: Most celebrations include special foods, enjoyable activities and a special focus on children. Preschoolers can learn that all people have a great love for their children and enjoy doing fun activities together, even if they have different looks, beliefs and traditions.

Explaining Holidays Brings Understanding

Children notice differences and often wonder about them but may not always ask questions. During a time of talking about holidays and celebrations of different cultures, teachers and parents have a chance to open discussions about differences and give children a chance to develop an understanding of why people have different beliefs and practices. Some ways for children to learn about holidays in preschool or with parents are:

- Meeting People: Talking with adults and children who celebrate different holidays can be a wonderful way to understand not just the facts of a holiday but how it is practiced and what it means to the people who celebrate it. In a preschool classroom, children and their parents can share their own family holiday traditions and bring decorations or food to try.

- Doing Activities: Doing a craft, game or activity from a holiday celebration helps children explore and experience different holiday traditions in an age-appropriate way.

Holidays Bring People Together

Even within cultural and religious groups, there are often many differences of opinion about practices or beliefs, just as there are sometimes disagreements among family members. However, holidays are times that people can unite around something bigger than themselves. Learning about holiday celebrations, especially ones celebrated by other students in their classroom, helps children to develop an appreciation and understanding for what is important to their friends, neighbors and other people they meet in the community.

Explaining Holidays to Preschoolers Through Books

Parents and teachers can reinforce explaining holidays to preschoolers by reading multicultural holiday books. One benefit of reading holiday books to your children is that you will have the opportunity to explain your own beliefs and traditions and answer your child's questions. Better yet, you can learn along with your children if you don't know much about the holiday either. Here are some good books to start with:

- Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins (Eric A. Kimmel) is a creative adaptation of the story of the symbols and traditions of the Jewish holiday which adds an exciting twist while keeping the original spirit of the story.

- My First Kwanzaa (Deborah Chocolate) explains the traditions of the holiday by showing how a family celebrates their African heritage together with food, candles and extended family.

- Christmas Around the World (Mary Lankford) includes illustrations and short descriptions of how 12 different cultures celebrate Christmas differently.

- Bringing in the New Year (Grace Lin) follows the preparations of a Chinese American family as they get ready for the Chinese New Year.

- Diwali, A Cultural Adventure (Sana Sood) introduces the Hindu holiday with rhymes, colorful pictures and simple language.

Enjoy Learning with Your Child

Many adults have not had the opportunity to learn about the beliefs and cultures of other people, so take this opportunity to grow in understanding along with your child. Teaching children to value the cultural traditions of other people is an important part of raising a child with healthy emotions and social connections. Parents and preschool teachers can help children learn to be culturally sensitive by explaining holidays to preschoolers and helping them learn why different people celebrate differently.

Outsmart the Wiggles

by Preston Blackburn

When children reach elementary school, they’re expected to sit still so they can learn. With calm bodies and minds, they’re more attentive, receptive learners. But why do so many kids have ants in their pants, and how did they get there?

Turns out, the ants are usually a result of too much stillness during the early childhood years.

The Problem of Stillness

Young children in previous generations spent much more time doing big-body play. Since the early 2000s, we have had a fundamental cultural shift away from child-directed free play towards more sedentary endeavors.

What is wrong with stillness?

First, it is making kids weak. A 2013 study out of Australia found cardiovascular endurance in children is declining at a rate of 5% per decade. In 2013, it took children 90 seconds longer to run a mile than in the 1980s, leaving kids with 15% less cardiovascular fitness than their parents.

Additionally, a 2014 study from the United Kingdom found that core strength in children is eroding. Between 1998 and 2008 core strength declined by 2.6% per year, and between 2008 and 2014 it declined by 3.9% per year. Since these studies were published, we have had another decade and a pandemic. It is likely that the numbers are even worse now. But 21st century children’s bodies and brains need the same thing previous generations needed—to move.

Children begin life dominated by the right side of their brains, and as they grow, they develop a more balanced brain when the right and left hemispheres begin to converse and coordinate. This balance helps kids operate in a more logical and less emotional world. The very best way to develop this cross-brain conversation is through movement—the bigger the better. Simply put, big body play builds brains.

As well as laying the groundwork for academic achievement, big movement organically builds cardiovascular and core strength. It puts pressure on the joints and places the head in different planes to support proprioceptive and vestibular development.

Aerobic Movement

Consider aerobic movement. Aerobic movement improves cardiovascular fitness because the large muscles in the body force more oxygenated blood to circulate, improving the strength and capacity of the heart and lungs. That same aerobic movement also impacts the brain by causing the release of Brain Derived Neurotropic Factor (BDNF), a chemical that builds new neural connections, particularly in the area associated with executive function. BDNF improves cognition, memory, and motivation, improving children’s quality of play and communication skills.

In generations past, cardiovascular endurance was built in traditional play whether it was Kick-the-Can, Red Rover, pushing the merry-go-round at the playground, or riding bikes for hours. When kids don’t move enough, they don’t build cardiovascular fitness. Not only is their health compromised, but their behavior is affected, and later learning is harder.

Core Strength

Core strength is also critical in children’s development. With a strong core, children have smooth-moving and controlled appendages. For adults, core strength is vital to functional movements like swinging a golf club and carrying laundry baskets. For children, a strong core encourages positive participation in active play and in turn, supports their future academic success. A child with poor core strength will struggle with both, leading to a loss of confidence in play and academic struggles later in life.

When children get to elementary school, they are expected to spend extended periods of time seated at a desk. Without a strong core, sitting is uncomfortable, leading to shifting and wiggling—those dreaded “ants in the pants”—that are a distraction and make attentiveness in class difficult.

In previous generations, children built core strength in all kinds of play: swinging, sliding, climbing, building forts, digging in the sand, and playing on the monkey bars. But children who do not move enough cannot build this strength. They will wiggle in discomfort, making school tasks harder than they need to be.

Too much stillness also reduces the opportunity for the body to explore its surroundings, feeding essential information to the brain. As a culture, we tend to treat the body as simply a vessel for carrying around our hard-working brains. In truth, the brain needs the body in order to develop. Movement informs and shapes the brain in important ways that facilitate learning.

Sense of Force

Consider the proprioceptive system, housed in the joints, giving children a sense of force. Through a variety of play experiences children begin to grasp the difference between the amount of force needed for petting a kitten versus kicking a ball. They learn the amount of force they need to use for squishing modeling clay versus the gentle pressure needed when putting pencil to paper without breaking the tip.

When children don’t push, pull, jump, or climb, they do not put pressure on their joints. This limited physical experience thwarts the development of the proprioceptive system and restricts their understanding of force, leading kids to use too much force (hitting instead of tagging), or too little (tapping instead of pressing). Without enough movement to develop the proprioceptive system, children’s brains will search out this stimulus in other less productive ways: slamming into walls and floor, excessive roughhousing, and pushing heavy things over. These actions may look like bad behavior, poor self-regulation, or a lack of self-control. But, more likely, children demonstrating these behaviors are desperately seeking essential information about the body and how to use it. Movement is the only source of that critical information.

Balance and Movement

When children are still, they spend a great deal of time upright. But children need their heads to move in multiple planes and directions to develop their vestibular system, within the inner ear. This is the sense of balance and movement. When this system is well-developed, children innately know that while they’re moving, the rest of the world is still. This sense is best developed through spinning, swinging, sliding, hanging upside down, log rolling, and somersaulting. These movements hone children’s focal point, the ability to hold a steady gaze while in motion, helping them feel stable.

Adults who have had damage to their vestibular system from infection or stroke will tell you it feels like the world is constantly moving. Imagine being a child trying to climb the ladder on a slide when the ladder seems to be moving. Later in the classroom, a weak focal point will cause letters and numbers to jump around on the page or board, making reading, writing, and math hard to master.

Additionally, the vestibular system is part of the data management center. Children are bombarded with information all day long, but a strong vestibular system helps them filter the important from the unimportant. Without that filtering, all sensory information is equally important. The hum of the air conditioning is the same as the teacher’s voice, and the world is overwhelming. The only answer is to shut down. The only way to turn the vestibular system back on is to move—a lot—in many different ways.

Instead of shutting down, some children with weak vestibular systems will be in constant motion, running or spinning, to feed their brains the information they desperately need to hone a focal point and manage data. And what does this motion look like in a classroom? It looks like the child is experiencing bad behavior, an inability to self-regulate, and poor self-control. In reality, their brain is screaming for information about the body and how to use it. Healthy proprioceptive and vestibular systems build the foundation for rich play and learning.

Ideas for Play:

Cardiovascular endurance:

Tag games: There are countless versions of tag, and children love them all. Even toddlers love a good game of chase.

Core strength:

Any play that incorporates the whole body improves children’s core strength, from bear crawling to bike riding to swimming. Playgrounds provide opportunities for building forts out of stumps and branches or climbing trees. Full body work is core strengthening.

Proprioceptive:

Heavy chores and heavy play strengthen children’s proprioceptive systems. Here are some examples: taking out the trash, stomping the recycling, carrying laundry baskets, running uphill, hanging from monkey bars, climbing, carrying buckets of sand or water, pushing or pulling a full wagon or sled.

Vestibular:

Activities that build a strong vestibular system: Swinging, sliding, hanging upside down, spinning, riding scooter boards, sledding, pushing wagons, doing somersaults, log rolling, cartwheels, bear crawling.

Conclusion

Big-body play is cheap. It is innate. It is available whether you have a big space or a small space. It is what children crave and it is what children need.

Sadly, children are paying the price for a lack of play with increased weakness, more behavior challenges, and a harder time in school.

Let’s get out of the way and let the kids play!

Practicing Social Skills: Activity Ideas for Toddlers

by Help Me Grow

Social skills, like learning how to play with others and taking turns, begin to develop at a young age. Coaching and interaction from caring adults are important ways that children learn these skills.

Learning social and emotional skills helps children understand others and develop relationships, and it takes time and practice. You can help teach actions and words to use with others so your child can communicate their needs, wants and emotions. Routines help children feel safe and secure as they try new things.

Children begin to learn important social and emotional skills at a young age. Here are ideas to help toddlers from 12 months to 3 years develop these skills.

- Play games or sing songs that toddlers can sing with you, copying your sounds and body movements. Sing favorite songs repeatedly. Toddlers enjoy repetition.

- Read books or tell stories to toddlers using a quiet voice. Point to the words and pictures in a book as you read. You might say, “Remember when we did ____? That was kind of like what they are doing in this story.”

- Have a toddler pick a toy or stuffed animal, and then hide it somewhere for them to find. Help the toddler find it. Add a flashlight for more fun.

- Look at photos. Name the people and talk about what was taking place at the time. Young children enjoy looking at photos of themselves and pictures of other children.

- Take turns rolling a toy car or ball back and forth. Talk about what you are doing as you play a sharing activity together.

- Play games with toddlers, such as taking turns jumping off the bottom step, kicking a ball or blowing bubbles. Taking turns is essential to good social skills.

- Play make-believe with stuffed animals and toys. Take turns telling a simple story with the animals or toys. Even a young toddler can share by telling a story, even if you don’t understand the words he is trying to say. It is fun and builds early communication and language skills.

- Take turns handing toys back and forth to each other. Name the toys as you pass them. Add the words “please” and “thank you” as you pass the toys.

- Be consistent with what you let toddlers do. Let toddlers know when you appreciate what they are learning to do and when they are helping, such as picking up toys or bringing their plate to the sink.

The Earlier the Better? Why academics on young children is counterproductive.

by Rae Pica

A mother told me her son was seven months old when she first felt the pressure to enroll him in enrichment programs. She said, “Here I was with an infant who had just learned to sit upright by himself, and someone was asking me what classes he was going to be taking, as if he were ten!”

A few years back, the San Francisco Chronicle told the story of one woman who called a popular preschool to say she was thinking about getting pregnant and wanted to put her baby-to-be on the school’s waiting list. I learned of another mother who enrolled her child in “preschool prep”—at four months old.

What these stories have in common is the belief that earlier is better. You just can’t start kids too soon on the road to success. And it’s not just parents who believe it. As stated by Nancy Bailey in an article titled “Setting Children Up to Hate Reading”:

"Politicians, venture philanthropists, and even the President, make early learning into an emergency. What’s a poor kindergartener or preschooler to do when they must carry the weight of the nation on their backs—when every letter and pronunciation is scrutinized like never before?

Unfortunately, many kindergarten teachers have bought into this harmful message. Many have thrown out their play kitchens, blocks, napping rugs, and doll houses believing it is critical that children should learn to read in kindergarten!"

Kindergarten, according to studies from the American Institutes for Research and the University of Virginia, has become “the new first grade.” And, based on my observations, preschool has clearly become the new kindergarten. The directors and teachers in private preschools all around the country tell me that parents are putting increasing pressure on them to switch from play-based to academic-oriented curriculums. If the schools don’t submit to the parents’ wishes, they risk losing enrollment to those schools that do favor early academics.

The belief that earlier is better has become deeply ingrained in our society. Parents are terrified that if they don’t give their little ones a jump-start on the “competition,” their children will fall behind and end up as miserable failures. Politicians pander to the ridiculous notion that education is a race. And teachers—from preschool to the primary grades—are being forced to abandon their understanding of what is developmentally appropriate and teach content they know to be wrong for kids.

And what happens to the kids? They’re too often stressed and miserable. Depression among children is at an all-time high. Children taught to read at an early age have more vision problems, and those taught to read at age five have more difficulty reading than those taught at age seven.

And of course, reading isn’t the only skill children are being asked to acquire too early; requirements in all content areas have risen as curriculum is “pushed down” from higher to lower grades. Anxiety rises as children fail to meet their parents’ and teachers’ expectations—because they’re developmentally incapable of doing what’s asked of them. All of this does nothing to endear them to learning.

So, the end result is often the same: loss of motivation. Demanding that children perform skills for which they’re not yet ready creates fear and frustration in them. Moreover, children who are “trained” by adults to develop at a pace that is not their own tend to become less autonomous people.

And here’s the punchline: child development cannot be accelerated. Moreover, there’s no reason to try to accelerate it. The research shows that usually by third grade, and certainly by middle school, there’s no real difference in reading levels between those who started reading early and those who started later.

As to the play-versus-academics debate in early learning, studies have also determined that children enrolled in play-oriented preschools don’t have a disadvantage over those who are enrolled in preschools focusing on early academics. One study, in fact, showed that there were neither short-term nor long-term advantages of early academics versus play and that there were no distinguishable differences by first grade. In another study, fourth graders who had attended play-oriented preschools in which children often initiated their own activities had better academic performance than those who had attended academic-oriented preschools.

But no one in charge is paying attention to the research. Given that, here are some of the concerns I have:

- What’s to ensure children won’t be burned out from all the pushing and pressure before they’ve even reached puberty?

- If we’ve caused them to miss the magic of childhood, how will kids ever find the magic necessary to cope with the trials and tribulations of adulthood?

- What will become of the childlike nature adults call upon when they need reminding of the delight found in simple things—when they need to bring out the playfulness that makes life worth living?

- At what cost will all of this “pushing down” come?

Childhood is not a dress rehearsal for adulthood. It is a separate, unique, and very special phase of life. And we’re essentially wiping it out of existence in a misguided effort to ensure children get ahead.

When did we decide that life was one long race? When, exactly, did life become a competition?

What’s a Teacher to Do?

- Just say no. As I like to tell my audiences, there are more of us than them. We have the power—including the political power—to stop the insanity. Become involved in policy at whatever level you can. Sign online letters and petitions addressed to policymakers. Join forces with groups such as Defending the Early Years because there’s power in numbers in doing so. Refuse to vote for senators, congresspersons, governors, mayors, or school board members who do not support good education policy and practice.

- Get parents on your side. Educate them about the fallacies behind the belief that earlier is better. Don’t be shy about pointing out the potential problems inherent in trying to hurry child development.

- Despite what’s happening around you, plan your curriculum and use teaching practices based on the research, not on the nonsense being promoted by those who don’t know any better.